Why did Rome fall? Historians and intellectuals have been debating this question for centuries. A recently published study sheds new light on the controversial topic of the fall of the Roman Empire. The researchers think that non-European immigration may have played a central role.

By Jonas Greindberg

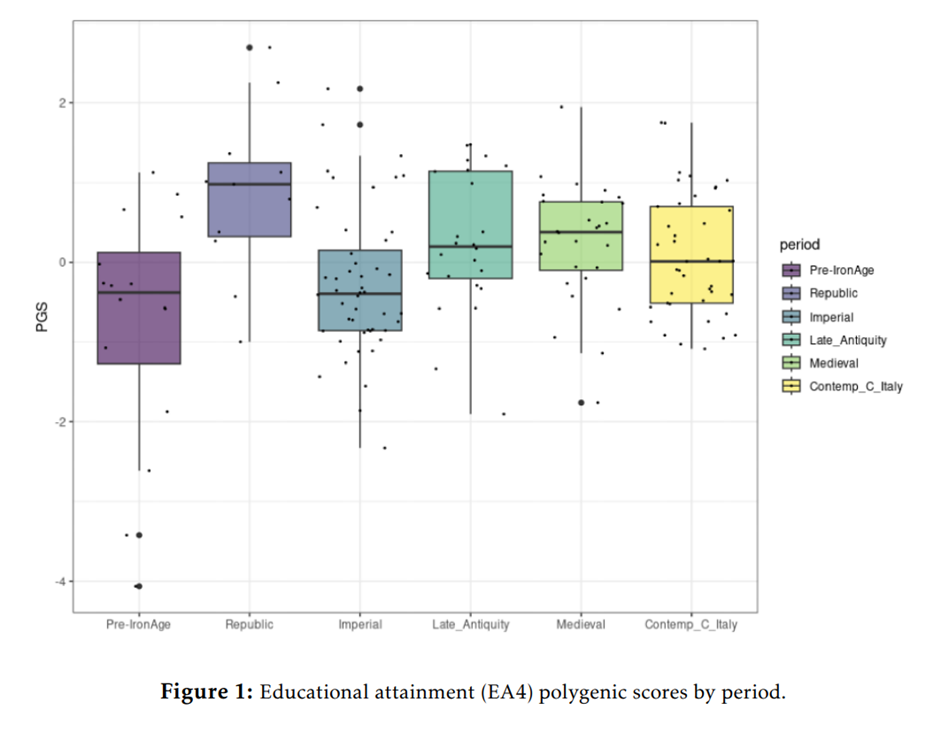

An international team of researchers has studied the genome of 127 persons who lived in central Italy from the Neolithic Era to the early Modern Era. Genomic changes suggest that cognitive abilities peaked during the Roman Republic but declined sharply during the Imperial Era. The researchers think this change might be related to immigration from non-European areas.

Mainstream academics cry out in pain

The study by the evolutionary biologists Emil Kirkegaard, Davide Piffer, and Edward Dutton led to a chorus of outrage among mainstream academics: the three scientists do not produce genuine research, the Twitter academics Will Barrie and Adam Rutherford responded. Instead, the three scientists would peddle “scientific racism” in a “fake journal”. The Heimatkurier, therefore, takes the liberty to take a deep dive into the study “Intelligence Trends in Ancient Rome”.

Measuring Ancient intelligence

The study uses findings from genome-wide association studies to compare patterns in 127 samples of Ancient DNA with present-day DNA that allow inferences about educational attainment. The researchers base their approach on a mainstream publication, according to which intelligence is genetically heritable by up to 80 percent.

Although the study sample of 127 persons is relatively small for a time frame of over 12,000 years, it should be noted that this study represents an important first step in the study of Ancient Roman intelligence. It is to be expected that future research, mainly in the field of archaeogenetics, will provide researchers with more robust data for further studies.

According to the study, Antique DNA had the lowest “polygenic score” for educational attainment prior to the Bronze Age. Polygenic score is a ranking determined by the frequency of genetic variants that correlate with the phenotypic formation of a trait – in this case, educational attainment. The polygenic score peaked in the Republic, declined sharply in the Imperial Era, and rose again slightly in Late Antiquity. From Late Antiquity to the present, this score has not significantly changed and still remains far below the Roman Republic’s peak.

The rise and fall of Roman intelligence

What explains the decline in intellectual abilities since the Imperial Era? The researchers suspect that the Roman Republic was a victim of its own military success: Roman domination over the Mediterranean enabled the mass importation of non-European slaves to Rome from 100 B.C. onward. Ever more miscegenation with the native population led to a decline in cognitive abilities, the study concludes.

Parallel with modern replacement migration?

Edward Dutton told the Heimatkurier that the current replacement migration to Europe has parallels with the studied process. Both the Roman Empire and today’s Europe are in a “winter of civilization,” he said. As a result, ethnocentrism and religiosity are losing ground. This materialistic mindset is typical of late civilizations and a contributing factor to mass immigration. Since “IQ is 80 percent hereditary,” Dutton remarked, replacement migration from non-white countries will significantly lower the IQ of European host countries over time.

Dysgenic welfare

According to the study, another reason for the decline in intelligence in Ancient Rome was a dysgenic welfare state. Already in 123 B.C., the Republic established public welfare programs to feed the city of Rome. The Imperial Era saw a massive expansion of these programs until 200,000 people were regularly fed by the state. The increased reproduction of less intelligent people caused a gradual decline in intellectual abilities, the researchers conclude.

The Germanic reversal

A reversal of these dysgenic trends occurred only with the conquest of Rome by Germanic peoples during the Migration Period in Late Antiquity. The researchers conclude: “The collapse of the Roman Empire was accompanied and accelerated by an influx of Germanic people which settled in Italy and changed its genetic landscape. This influx can explain the slow rise in the polygenic scores of Late Antiquity and into the Medieval period, which partly reversed the decline observed in the Imperial Period.”

Roman intelligence in Roman art

A look at art history seems to confirm the study’s finding that a general decline in intelligence occurred in the Imperial Era. The statue of Augustus of Primaporta dates from shortly after the end of the Roman Republic and serves as one of the greatest monuments to Roman artistry. The sculptor demonstrates his mastery with fine facial features of the primus inter pares, stunning details on the breastplate, and the realistic drapery of the toga.

In contrast, the bust of Maximinus Daia at the beginning of the 4th century shows the image of a coarse monster. With rough chisel strokes, an unmotivated artisan has indicated hair and a designer stubble. The drapery has nothing of the playful elegance of its Augustan predecessor. The piercing madness of a soldier-emperor, in whom ancient historians suspected a migrant from Illyria, glares at the beholder with widened glowering eyes.

Did Ancient replacement migration lead to the collapse?

From the reign of Augustus and Maximinus Daia lay a good 300 years of mass immigration from North Africa and the Middle East to Rome. This demographic change was sealed by the Syrian-African emperor Caracalla, who in 212 granted full citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Roman Empire. British historian Peter Heather suggests that the mass immigration of foreign barbarian peoples led to conflicts that made it increasingly difficult to maintain complex systems.

A sad consequence of this civilizational collapse can be seen in the contempt for scholarship and open debate: In 529, Byzantine emperor Justinian I had the Platonic Academy closed forever. With this, the free spirit of Greek thought left the world for almost a millennium, until it was reawakened by the descendants of the Germanic Lombards in northern Italy.

About the authors of the study

Edward Dutton is a British researcher specializing in evolutionary biology and intelligence research. Dutton earned a PhD from the University of Aberdeen in 2005 for a study on Christian fundamentalism. Since 2019, Dutton has been an editorial board member of the journal of evolutionary psychology, Mankind Quarterly. Dutton is the author of several nonfiction books, which can be ordered here.

Emil Kirkegaard founded the online publication platform OpenPsych with Davide Pfiffer in 2014. OpenPsych enables peer-reviewed and free publication of scientific papers, which are currently still opposed by the academic mainstream due to political correctness. OpenPsych focuses on differential psychology and behavioral genetics.

Davide Pfiffer is an Italian evolutionary biologist and co-founder of OpenPsych. Pfiffer has also published in mainstream publications such as Thinking Skills and Personality and Individual Differences. Since 2012, Pfiffer has published primarily in publications such as Mankind Quarterly and Open Behavioral Genetics, which are not subject to censorship by political correctness.